Ellen Boyd

“The connection between the internet and found footage horror is strong,” writes Shellie McMurdo. Yet despite over 20 years of internet connection, the most famous instance of online found-footage horror happened in 1999 when The Blair Witch Project’s (1999) website went live before the release of the film. The website contained information about the missing (presumed dead) filmmakers, interviews with authorities on the case, information about the Blair Witch legend, etc. But the Blair Witch Project website was far from alone. Just two years earlier, The Last Broadcast (1997) uploaded a website to expand the film’s investigation of the death of local cable TV hosts and wrongful conviction of their supposed killer. The Collingswood Story (2002), filmed entirely via video-chat, would post a website detailing the legend of Alan Toshi, a cult leader responsible for the deaths of the film’s protagonists just a couple years after Blair Witch. Both of these websites include many of the same elements—timelines, collections of analog documents like woodcuts and photographs, video interviews, etc.—that expand the lore of their respective legends and events beyond the scope of the films.

Despite the wealth of text here, most critics tend to focus on The Blair Witch Project website’s success in marketing the film. Though true, this angle ignores consideration of the website as a text in itself. While McMurdo does a thorough investigation into found footage websites in the wake of Blair Witch, she cites “a critical need in scholarship surrounding the found footage horror subgenre to move on from a tendency to focus on the marketing of this one film” (159). J. P. Telotte pays some attention to other websites in his chapter “The Blair Witch Project: Film and the Internet,” in which he analyzes how The Blair Witch Project website separates itself from other promotional websites by establishing a complex “back-story” of the Blair Witch legend and filmmakers. This “suggest[s] that we see the film not as film but as one more artifact, along with the materials gathered together at the Web site, which we might view in order to better understand a kind of repressed or hidden reality” (42). In this reading, not only is the primacy of film as a narrative medium disrupted, but so is the space of the movie theatre, which gets positioned on the same level, perhaps even subordinate to, the space of the home. The Collingswood Story, especially, represents a shift to the smallest screen at the time—the computer screen—as it was filmed via video chatting. For both of these found footage films, film and the theatre are no longer sufficient on their own: other “artifacts” are needed to uncover a “repressed or hidden reality” that could explain what happened to the filmmakers or what lies behind their respective legends. Indeed, these multimedia archives propose that connecting these artifacts and the public is the best way of locating a truth. At the same time, though, the lack of central text in this paratextual network means that there is also no central authoritative text that users and viewers can turn to in order to verify the information they receive, creating anxiety as to whether the truth that’s asserted is one that can be trusted.

This lack of central authority, inherent in the networked structure, links these websites with elements of the digital archive effect outlined by Jaimie Baron. While Baron is discussing non-fictional digital archives, these three ‘found-footage’ websites mimic the elements she describes. What distinguishes the digital archive, Baron claims, is not what’s in the archive “but rather in the different relationships (or potential relationships) enabled and established among these contents by both archons and users” (141). In other words, the possibilities that can arise out of the interaction between users and archival documents is a defining feature of the digital archive. In Baron’s chapter, digital archives extend to “unofficial archives such as Youtube” (Baron, 139) which trouble the official archive because “anyone can post anything to YouTube anytime, so there is no unified oversight by a single organizing entity or even significant principles of collection” (Baron 139-140). Furthermore, this unsupervised uploading in unofficial digital archives creates databases of “archival excess” (142) that, absent any official organizing authority or contextual coherence (143), rely more on the user to make meaning of them than archival structures to give meaning. The first part of this paper contends that found-footage websites utilize these elements of the digital archive effect—interactivity, interconnectivity, excess, and an absent central authority—in order to engage the audience and convince them of their content’s authenticity, as well as to use these elements to bring horror closer to home.

That these websites open up new opportunities for interconnecting users and the possible horrors that await them positions the websites as early entries into digital horror. Digital horror, as defined in Xavier Aldana Reyes and Linnie Blake, is “any type of horror that actively purports to explore the dark side of contemporary life in a digital age governed by informational flows, rhizomatic public networks, virtual simulation, and visual-hyper simulation” (4). The second part of this paper focuses on how these websites—rather than using interconnectivity to create a benevolent, cooperative archive, as some believe is possible—instead represent early anxieties about what and who becomes accessible to you—and, perhaps more frighteningly, what and who gains access to you. In networked systems, you never know the intentions of the person (or entity) on the other side. At a time (the late twentieth century) when anxieties around technology were running rampant—especially with the approach of Y2K—these websites offer a snapshot into early formulations of digital horror and appropriations of digital archival sensibilities. But perhaps even more terrifying than apparently unlimited access to the horrors on the screen is the fact that these websites have now nearly disappeared from the internet, raising questions about the stability of what we preserve online. The last part of this paper begins to explore what it could mean to become a digital ghost in a place where things are supposed to never die.

“This is still being compiled”: Found footage websites as digital archive mimics

Both McMurdo (161-62) and Telotte (43-44) argue that a distinguishing factor of internet-based digital horror is the user’s ability to assert agency when interacting with the website’s content. Elements like The Blair Witch Project’s chatroom (now defunct) and The Last Broadcast’s invitation for users to email information to the filmmakers allows users to assert their own theories concerning the events of these paratextual archives.

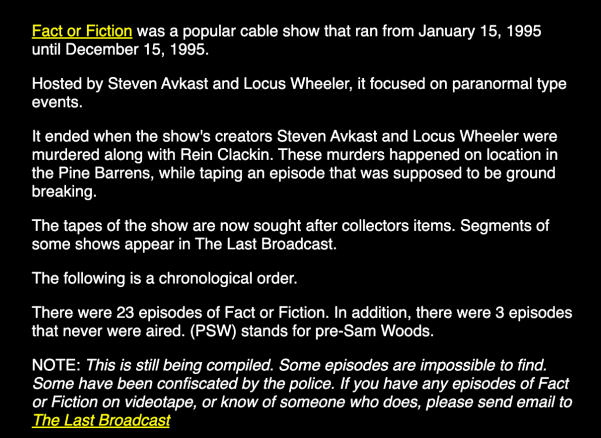

These websites are employing early forms of crowdsourcing that allows users to entertain themselves and engage with the site longer. Users are allowed to govern “how much they want to be creeped out” (Telotte, 44). This engagement is enabled by the fact that the website’s lack of a central organizing authority creates ambiguity as to how the documents are supposed to fit together. That users have the ability to interact with an excess of material conjures the veneer of authenticity and authority: they have access to about the same amount of information as official investigators are, and thus are given a similar level of authority. While the websites do have timelines and loosely categorized subpages, there is no explicit order in which the user must engage with the materials. You can begin with the timeline, jump to photographs, and then read Heather’s Journal or examine the episode list for Fact or Fiction, or vice versa. Other materials are provided with simplistic subtitles, while some are placed with almost no context at all.

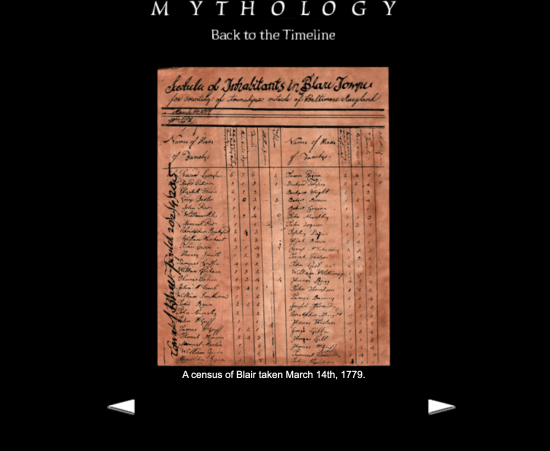

A census of the town of Blair from 1779 from The Blair Witch Website. The reasons behind including documents like this are left ambiguous, and up to the user to decide how it fits with the Blair Witch legend.

The minimal contextual information surrounding the documents has the potential to transform these websites into an archive of “nonsense” (Baron 146), where documents and objects do “not add up to something we consider contextually meaningful” (146) or give a complete answer. The dizzying amount of information makes the websites seem comprehensive, and thus it is less likely that users will feel they need to spend time debunking every single document. Their labyrinthine structures of links within links, dead ends, vague wording, etc. undermine the user’s ability to find a central truth. Even if users spend time combing through every document, they will undoubtedly remain l unsure whether the Blair Witch is real or the man in the attic (in The Collingswood Story) was really Alan Toshi. The found-footage hallmark of proven-yet-unproven truth is experienced first hand through these websites, then, as users attempt to put together scraps of information themselves. Here, interactivity and material excess work to the filmmakers’ benefit as they simulate a feeling of authority and authenticity that makes the stories seem more believable. They also, however, destabilize the idea that if we continue making more and more information available, then we will be able to find some sort of truth in its plenitude.

“I’ve updated this page with new info”: Found footage websites as digital horror

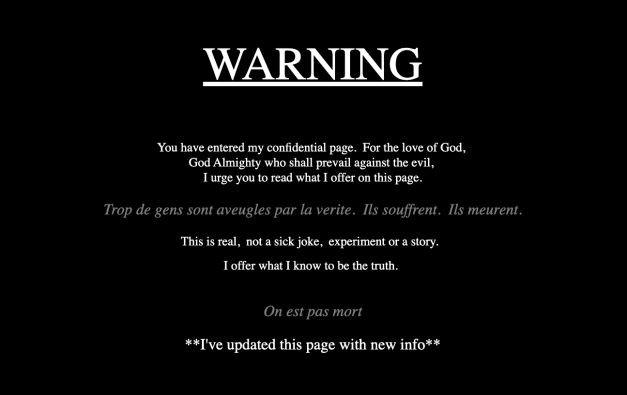

If interactivity keeps users on the websites longer, it takes a darker turn as these websites confront their users with the dangers of connecting with each other online. As web-based paratexts, the websites inherently “infiltrat[e] . . . safe zones outside of the films themselves” (McMurdo 162). Timelines on The Blair Witch Project and The Collingswood Story’s websites show plot points that extend beyond the endings of the films, thus refusing any sort of containment and closure even after audiences have left the theatre. This refusal of the events of the film to be contained is compounded by the means of accessing the website—the computer. The lack of containment is amplified, moreover, by the websites’ temporality: they are able to be updated, and with each update the possibility that there is a new horror, a new victim—and this next victim could be you. From the home, school, or library computer, users are always just a click away from encountering the horrors of the Blair Witch, Alan Tashi’s cult, or a serial killer. By nature of the medium, the content of the website can follow you anywhere there’s an internet connection, conjoining the real and digital world, putting one especially at risk for having their “safe zone” invaded. This is especially true in the cases of The Last Broadcast and The Collingwood Story websites. The website of The Last Broadcast was made by David Leigh (David Beard), who is revealed in the end to be the real killer of Steven Avkast (Stefan Avalos) and Locus Wheeler (Lance Weiler), murders for which he was never apprehended. Since the film posits that the events that led to Avkast and Wheeler’s death were triggered by chatting with people online, users risk that same fate when interacting with or emailing information into The Last Broadcast website. The Collingswood Story’s website pushes the anxiety about who you’re connecting with via the internet even further. When you enter the website you see that the home page is titled “WARNING”—it implies that just being on the website puts one in peril.

The Collingswood Story website is not from the perspective of the filmmakers, but is maintained by Vera Madeline (Diane Behrans), the psychic and former Alan Toshi cult member/victim. The website has a link to Madeline’s chatroom, where users can video chat with her, just as the main characters did. This is especially dangerous as it’s chatting with Madeline that led Rebecca (Stephanie Dees) and Johnny (Johnny Burton) to investigate the cult, which led to their deaths. The final image of Johnny sitting in front of the computer screen with his eyes gouged out could become the fate of the website users if they choose to chat with Madeline.

Johnny killed through his computer screen, a fate that could await The Collingswood Story Website users.

Lingering on the website or chat increases the chance that the horrors become only a few clicks away (Though, this threat is ultimately foreclosed as, when the user clicks the link to the cam, they are met with a link that claims the psychic has “temporarily shut down this site for personal reasons”). The implications here is that, through online networking, an unsuspecting user is just a few clicks away from unleashing horror into their own lives, as many of the protagonists did in these films. Though the recovered films, journals, blogs, photos, etc., are relics of the past, these websites threaten to update them into the future—possibly your future—if you aren’t careful enough. This anxiety that your computer or the internet could bring about the end is reminiscent of fears surrounding Y2K at the time—where people believed that it was a glitch in the online banking system that could bring about the end of the world. At once a point of access and ease, they were also a point of unease and showed how people interpreted the digital world as having real, detrimental consequences.

These files are no longer supported: Disappearance from the internet

Yet despite the prescience of the horrors and anxieties these websites elicited at the time they were uploaded, none of them exists in their original form anymore, and certain unsupported media like video and audio files are possibly lost forever. When reading McMurdo’s chapter, it’s hard not to notice how many of the websites she analyzes are also defunct. Though The Blair Witch Project website is still accessible through the Wayback Machine, certain media are unable to be accessed.

It is hard not to get a creepy feeling going through the shells of websites filled with dead media and links to nowhere: they conjure the haunting feelings that Jeffrey Sconce associates with our perceptions of the technological in-between. The way these websites unintentionally fade into the ether of the internet represents “digital horror[‘s] concern . . . with the disposability of recorded images, but it acknowledges that a form of haunting may also reside in those images’ abilities…to be ‘easily archived and dispersed” (Reyes, 3). While crowdsourcing and a web-based medium increases engagement and makes it easy for documents to be copied, pasted, uploaded, and downloaded, their ease of access and excess also makes these documents less covetable and more disposable. This creates a paradox for the digital archive and for found footage—the plethora of information, and the wider accessibility of it, can end up increasing the likelihood of its eventual deletion instead of its being conserved for posterity like the protagonists hoped. If interconnective access and documentative excess cannot prevent these websites’ gradual disappearances from search engines, then they confront us with the instability of the digital document. Baron warns that without updating, the digital archive and its information will disappear. But even if websites and documents are updated, this does not prevent instability: can those updated versions be considered the original, or authentic, or do they become digital palimpsests of what came before? We often ascribe a sense of permanence to the internet—how many times have we heard that once something is uploaded to the internet, it remains there forever? But twenty years also barely scratches the surface of the average lifespan in the US. Thus, though we ascribe permanence to the archive, Baron warns that we could soon be looking at an internet that reflects only recent history, leaving records from so many years ago blank (153-54). This is one of the largest fears that the found footage genre seems to try to abate—the fear of erasure. And lastly it also raises questions about what gets preserved, and therefore what gets to become part of a cultural memory.

This lack of preservation is a horror within itself: today we are so used to documenting our lives that the idea that it might all disappear one day is nearly incomprehensible. The gradual disappearance of these websites from the front pages of Google searches and the short-term memory of the internet may be reasons why they have faded from the digital cultural consciousness. But new website based horror projects have not really risen to take their place, at least, not with the same pull as The Blair Witch Project’s. This could be because these websites hit at a time when primitive digital literacy combined with cultural anxieties around the internet to make this a novel creative outlet. It could also be that many of the techniques we see these websites use—inviting users to speculate, providing an excessive amount of documentation, blurring the line between reality and what users see on the screens (both small and large)—are now a common part of the internet that users must navigate daily. Most recently, these aspects of the internet have been given attention because many of these techniques are also how conspiracy theorists and misinformation moguls use the internet in order to further political agendas or make money. This spillage of fictional manipulation of the truth by found footage has found a real foothold in the digital sphere, perhaps making people both more averse to it, but also more inured and used to wading through and dismissing (or, conversely, becoming enraptured by) misinformation online. While this is depressing, it also gives us a new reason, and a new urgency, to analyze internet found footage and the techniques it relies on, as the boundaries between what’s recorded and what’s real increasingly rot away.

Works Cited

Aldana Reyes, Xavier and Linnie Blake. “Introduction: Horror in the Digital Age.” Digital Horror: Haunted Technologies, Network Panic and the Found Footage Phenomenon, edited by Xavier Aldana Reyes and Linnie Blake, I.B. Tauris, 2016.

Avalos, Stefan, and Lance Weiler. The Last Broadcast. 1998.

Baron, Jaimie. “The Digital Archival Effect: Historiographies and Histories of the Digital Era.” The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History. Routledge, 2014.

Costanza, Mike. The Collingswood Story. 2002.

McMurdo, Shellie. “Death in digital: found footage horror and the internet”. Blood on the Lens: Trauma and Anxiety in American Found Footage Horror Cinema. Edinburgh University Press, 2023.

Myrick, Daniel. Sanchez, Eduardo. The Blair Witch Project. 1999.

Sconce, Jeffrey. Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television. Duke University Press, 2000.

Telotte, J.P. “The Blair Witch Project Project: Film and the Internet.” Nothing That Is: Millennial Cinema and the Blair Witch Controversies, edited by Sarah L. Higley and Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock. Wayne State University Press, 2004, pp. 37-52.

The Blair Witch Project. www.blairwitch.com

The Last Broadcast. thelastbroadcastmovie.com

www.collingswoodstory.com