R. L Stine’s The Haunting Hour is an excellent – and distinctly underrated youth horror series. It ran for four seasons from late in 2010 until 2014 on Discovery Family and should definitely be talked about more than it is.

In this essay, I’m going to highlight some of the best episodes of the series – adding to the list over time. I’d love to hear from readers – and viewers of the series – what your favorite episodes are.

“The Dead Body,” written by Scott Thomas and Jed Elinoff and directed by James Head aired on December 25, 2010 in the series’ first season.

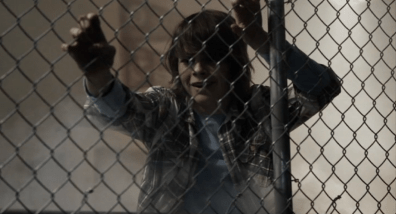

The episode takes on that classic topic of teen horror—bullying. Will Johnson (Brendan Meyer) is being bullied and finds unexpected help from a cool new kid, Jake Skinner (Matt Angel). Jake isn’t who he seems, however, and he has ulterior motives for helping Will: he wants something from Will. As the episode shifts back in time to 1961, to a fire that killed Jake, we realize what Jake wants from Will—and it’s nothing less than everything. This episode, like the best of The Haunting Hour episodes, evokes a horror of the classic genre: Carrie (Brian De Palma, 1976), a film about the enormous unforeseen consequences of bullying and casual cruelty in high school. As in Carrie, the chilling finale of “The Dead Body” takes place at a high school dance. And it is indeed a chilling finale, serving Will up with a fate he doesn’t seem to deserve. Just as Carrie dies in the fire she starts, doing nothing but perpetuate her own victimhood in her cataclysmic revenge, so too does Will propel his own status as victim. There’s no clear lesson here, which is what makes it a good episode.

“Red Dress,” also from season one (aired January 15, 2011) and also written by Scott Thomas and Jed Elinoff, directed by J. B. Sugar.

Another demonstration that the best of Haunting Hour’s episodes echo classic horror, “Red Dress” is a clear reference to Stephen King’s Needful Things (1991). As in King’s story, “Red Dress” works out with inexorable logic: good things need to be paid for. Best friends Jamie (Linda Tomassone) and Nicki (Eve Harlow) work at a snack bar frequented by rich kids. Jamie has a crush on one of the wealthy boys who frequents the club, and after stumbling across a beautiful red dress in a mysterious store called Raven’s Chest, she decides that she needs this dress to make the object of her adoration notice her. The blind store owner tells her, however, that the dress is $400, adding, “If you want something, you must pay for it.” Like so many girls in Haunting Hour, Jamie gets seduced by her image in the mirror, becoming sure that Zack (Ryan McDonell) would go for the girl in the red dress. So, she steals the dress.

The red dress—and its theft—forces a split in Jamie, as she becomes someone unrecognizable to herself and to her best friend. Zack does go for her, though, but Jamie doesn’t get to enjoy her victory because she must, as the store owner told her “pay for it.” Since she didn’t have $400, the price she pays for stealing the dress is much more—and more terrifying. As in other Haunting Hour episodes (including “The Dead Body”), “Red Dress” seems overly punitive: Jamie does not, in my view, deserve what happens to her. The episode is clearly trying to deliver an object lesson to teens about the sin of stealing. But, in doing so, it ignores the profound unfairness of class and wealth inequality. Jamie seems to be punished not only for theft but also for the crime of aspiring to move out of her designated economic position. In punishing theft so harshly, Haunting Hour delivers a conservative message about class along with its conventional morality tale.

“Really You” (Parts 1 and 2) – may be my favorite episode of The Haunting Hour, and the double episode inaugurated the show on October 29, 2010. Written by Billy Brown and Dan Angel and directed by Neill Fearnley, “Really You” is exceptional, beginning with a camera panning over severed doll parts and getting even creepier from there. It centers on Lilly (Bailee Madison)—a spoiled girl who has just coerced her father into getting her an expensive life-size “Really You” doll, complete with clothes and accessories that match Lilly’s own. At first, the plot is what you would expect: the doll, Lilly D, has a will of its own and engages in destructive actions that get blamed on Lilly. The episode does something different, though, testing not only Lilly’s character but her mother’s. Lilly has to learn whether she wants to be a selfish, spoiled, brat or a well-behaved considerate girl. As her mother says, “Which Lilly do you want to be?” But Lilly’s mother also gets seduced by the doll (even sleeping with it!), and she too has to learn that perhaps the model child is not a seemingly inanimate, inhuman (and thus impeccably well-behaved) doll. Lilly must learn to be good, while her mother must learn to love a less-than-perfect real human being. The episode thus tests more than one character’s desire for a static ideal.

Importantly, though, “Really You” also manages to weave in some for-real horror moments, including the always-disturbing animate doll shots. Indeed, one of these moments directly invokes Paranormal Activity (Oren Peli, 2007), as the camera Lilly’s brother has planted in his parents’ bedroom (where Lilly D sleeps), captures Lilli D sitting up and getting out of bed. Along the way, the episode provocatively suggests that there may be less of a difference than we think between the animate human and the inanimate doll. Watching “Really You” from the present moment – in 2023 – it’s striking how much last year’s horror success, M3GAN (Gerard Johnstone, 2022) is uncannily anticipated by this episode.

Lilly D makes a return in the later episode, “The Return of Lilly D,” at the end of season two (February 4, 2012), which is a much less interesting episode. The story takes a page out of the “Child’s Play” book and turns very quickly into an “evil doll is trying to kill me” plot, eschewing the psychological complexity of “Really You.”