It’s a moment of uncanny serendipity in horror film history.

The City of the Dead (re-named Horror Hotel in the US) – the first directorial project of Argentinian-born British director, John Llewellyn Moxey – was released in the UK in September 1960. Produced by Americans Milton Subotsky and Max J. Rosenberg, the film is generally considered to be the unofficial first of their Amicus Productions (a British company they would officially found shortly after the release of City of the Dead, and which had an impact on the horror genre in the 1960s that was second perhaps only to Hammer Studios)[i]. Filming commenced “at Shepperton Studios [in Surrey, England] in the Summer of 1959,” [ii] running at least through October.

The vastly more famous Psycho, produced and directed by Alfred Hitchcock, made at Universal Studios in the US and distributed by Paramount Pictures, was released in New York City in June 1960 and saw general distribution, like City of the Dead, in September 1960. Also like City of the Dead, filming began on Psycho in the later half of 1959 (running, specifically, between November 1959 and February 1960).

In other words, there’s virtually no way that either City of the Dead or Psycho could have influenced the other. And yet, they share some striking similarities. They are also, I should add, profoundly different in their approach to horror. Both these similarities and this difference are worth exploring.

So, what are the similarities between City of the Dead and Psycho?

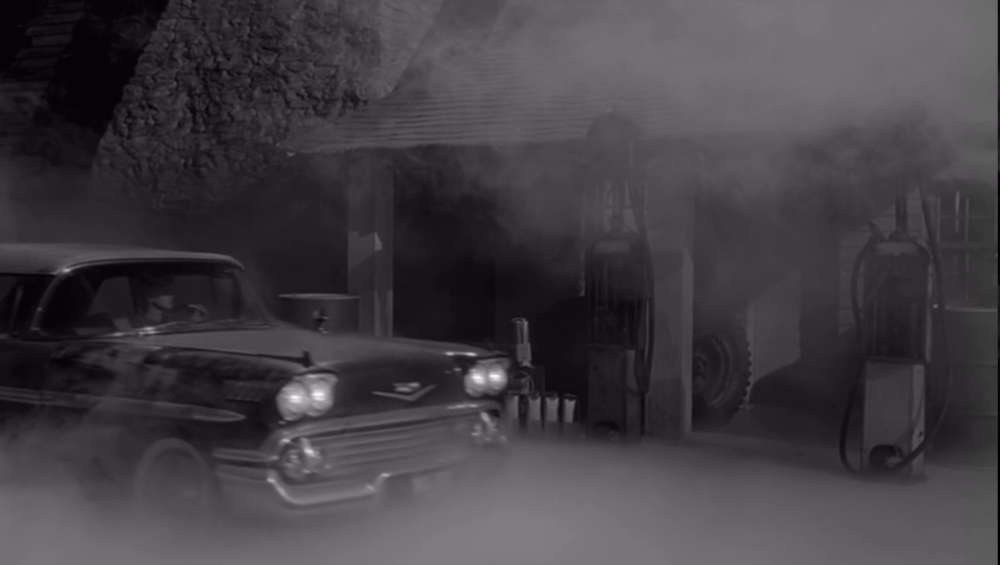

In City of the Dead, the ostensible hero of the film, Nan Barlow (Venetia Stevenson), drives out into rural America, specifically to Whitewood, Massachusetts, getting lost along the way but finally ending up at a lodge, the Raven’s Inn, where she blithely checks in, despite some strange behavior on the part of the owner. There are scenes of Nan driving; at one point, Nan is warned away by a gas station attendant who tells her that “Not many Godfearing folks visit Whitewood these days.” The village is “off the beaten track” and, in Whitewood, “time stands still.” In this place where time seems to have stopped, the character who has, so far, driven the forward movement of the narrative, will (shockingly) be killed at roughly forty minutes into the film.

In Psycho, the ostensible hero of the film, Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), drives away from the city and into the more isolated reaches of the (western) US, getting lost along the way but finally ending up at a motel. The owner of the motel tells Marion that “no one ever stops here” unless they’ve gotten lost. Since they “moved away the highway,” the Bates Motel has been literally off the beaten track, and the ‘stuckness’ in time of both the place and the man who lives there is all-consuming. In this place where everyone becomes caught in their own “private traps,” the character who has, so far, driven the forward movement of the narrative, will (shockingly) be killed at forty-eight minutes into the film.

The murder of Psycho’s ‘heroine’ – the character with whom the audience has been encouraged, if not compelled to identify – is one of the cinematic ‘shocks’ for which Psycho is justifiably lauded. City of the Dead, however, did it ‘first’ (if we look at the films’ production schedules). As Milton Subotsky proudly said, “we had the heroine get killed off halfway through the film and another girl going to look for her who finds herself in the same situation. This was similar to Psycho, but we did it first.”[iii]

As Subotsky notes when he asserts that “we did it first,” both City of the Dead and Psycho are also similar in what happens after their seeming protagonist is killed. In both films, a trio of characters follow after the missing women, moving, as those women had, from the space of rational modernity to that of irrational ‘stuckness’. In Psycho, it is, of course, Marion’s sister Lila (Vera Miles), Marion’s boyfriend Sam (John Gavin), and the private investigator Milton Arbogast (Martin Balsam). In City of the Dead, it is Nan’s fiancé, Bill Maitland (Tom Naylor), her brother and college professor Richard Barlow (Dennis Lotis), and an antiques dealer from Whitewood, Patricia Russell (Betta St. John), who go searching for the missing Nan. Although both Patricia (in City of the Dead) and Lila (in Psycho) find themselves in some peril in the second part of the film, in general, the weight of the narrative has shifted slightly from horror (with a lone, vulnerable woman at the center) to a more investigative plot, and, in each case, the combined forces of rational modernity ultimately defeat what has been entrenched in the isolated and ‘left behind’ place.

There are striking visual convergences between the two films, as well as similar plots and narrative structures. The heroine who drives the first part of the plot is sexualized; not only is she part of a heterosexual couple, but she is also displayed in a state of undress. Psycho certainly raised some eyebrows with its opening scene of Marion in her underwear – a sight that’s reprised two more times. Nan, too, is shown changing in her hotel room, appearing in her underwear; she and Marion thus mirror each other in scenes that directly precede their inexorable movement toward their dooms.

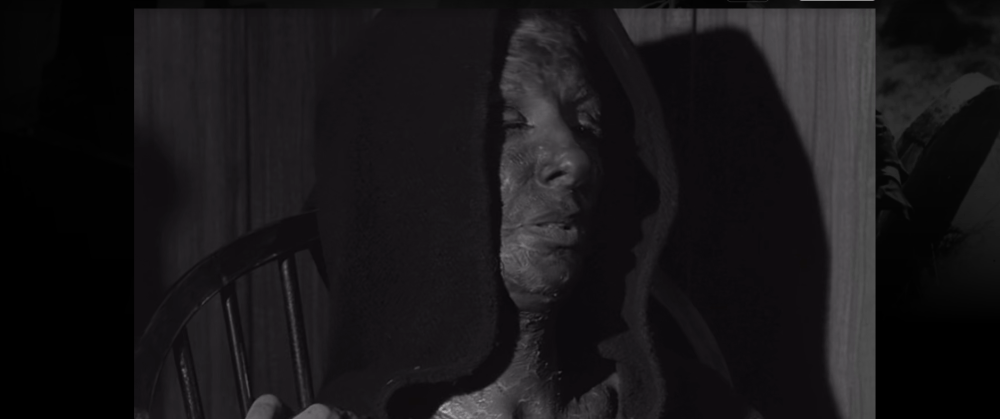

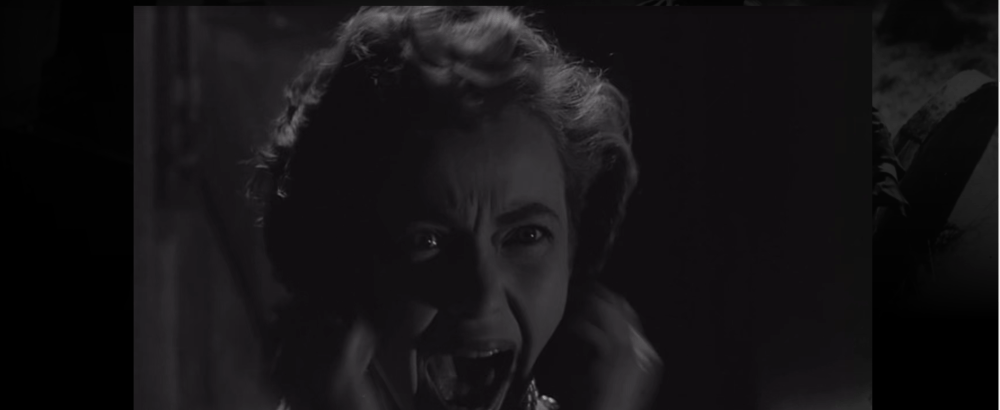

Finally, and really surprising given that these films could not have influenced each other, there is a parallel scene toward the end of the film, as the surviving characters have figured out the fate of the woman they seek and the secrets of the hotel / isolated location they came to investigate. In a famous scene in the cellar of the Bates home, Lila turns a chair around and is confronted with the mummified body of Norman’s mother; she shrieks. At the end of City of the Dead, Pat and Richard turn a chair and find the burned and mummified body of Mrs. Newless (Patricia Jessel), the innkeeper and reincarnated witch. Pat shrieks – in a virtual mirror image of Lila’s shriek in the fruit cellar in Psycho.

With all the similarities in narrative structure and plot, and with the uncanny mirroring of scenes that involve, especially, the female lead characters, there are significant and profound differences between City of the Dead and Psycho.

While the seeds of each film’s murders are rooted in the past (another similarity), City of the Dead invokes a communal history of witchcraft that stretches back to 1692 (significant as the date of the Salem witchcraft trials) when Elizabeth Selwyn was burned alive as a witch. Psycho’s past is a familial and psychological past, rooted in Norman’s individual family trauma – the trauma of losing his father, of ‘losing’ his mother to a lover, and the trauma of his own act of matricide. Indeed, Psycho is known as one of the first ‘modern’ horror films precisely because it shifts the register of horror to the personal, psychological, and familial.

City of the Dead and Psycho are also similar in that the past is not in the least bit past in either film. The past is very much ‘alive’ in the present; specifically, two powerful women who were killed not least because of their power (Elizabeth Selwyn and Mrs. Bates) live on (in some form) in the present. In the gothic narrative of City of the Dead, Elizabeth Selwyn gave her soul to Satan as she died in return for eternal life; part of the pact is the annual ritual sacrifice of a girl on Candlemass Eve. In Psycho, Mrs. Bates lives on in the psyche of the son who murdered her – and this uncanny afterlife also requires the sacrifice of girls, specifically any girl for whom her son feels desire. Interestingly, then, both films demand the sacrifice of young women as an integral part of their narrative, although the nature of the compulsion that drives this sacrifice is very different.

As much as Psycho inaugurated the modern horror film, and as much as City of the Dead has been largely forgotten, I would argue that it’s time to remember and re-watch the latter. Indeed, one could argue that City of the Dead is an incarnation of the folk horror that is currently so popular: it features an isolated town stuck in the past, driven by ancient and occult ritual, demanding of reiterated sacrifices.[iv] The ‘modern’ and educated characters (associated with academia and antiquarianism) are all stricken with horror at finding themselves confronting a ‘primitive’ way of life. Christopher Lee, who played both a college professor and a member of Whitewood’s coven, said about the film that it “did combine ancient superstition and ritual with modern university life.”[v] While Psycho is psychological and mired in the horror of family and sexuality, then. City of the Dead is mired in the horror of tradition and ritual that should be found only in history books about benighted and banished superstition.

Above all, though, City of the Dead – so similar to Psycho and yet so very, very different – certainly demands watching.

NOTES

[i] See The Dark Side Presents: Amicus: The Studio That Dripped Blood, ed. By Allan Bryce, Stray Cat Publishing, 2000, for a great introduction to Subotsky and Rosenberg and the origins of Amicus. See pp. 12-15 for a discussion of The City of the Dead.

[ii] The Dark Side Presents, p. 14.

[iii] The Dark Side Presents, p. 13. What Subotsky is not quite so direct about is that, while the timing of Marion’s murder was an aesthetic choice on Hitchcock’s part, in the case of City of the Dead, there was miscommunication about the nature of the film and so the original script was only sixty minutes long. In order to extend it to feature length, Subotsky “added the boyfriend who goes to look for Nan . . . after her disappearance” (13).

[iv] The writer of The Dark Side Presents asserts (with some truth) that “the film is remarkably similar in places to Hammer’s stagey 1968 black magic offering The Devil Rides Out” (15).

[v] The Dark Side Presents, p. 13.