Darren Gray

Found footage horror rarely features individuals with disabilities, however, it is a genre that manipulates and subverts ideas of what is perceived as ‘normal’ especially around concepts of embodiment. Alexandra Heller-Nicolas argues that the format creates “a space where spectators can enjoy having their boundaries pushed” and “where the lines between fact and fiction […] are directly challenged” (Heller-Nicolas 4). The format provides a subversive space in which understandings of fact/fiction and ‘normal’/‘abnormal’ are exposed and destabilised. Using Adam Robitel’s The Taking of Deborah Logan (2014), it will be shown how found footage horror can articulate deeply held anxieties around aging, illness, physical/mental impairment and expose the highly unstable and unreliable social categories of ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’.

Found footage horror is rooted in Gothic Literature’s assembled narratives. Frankenstein (1818), Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886) and Dracula (1897) all have extraordinary bodies at their core but are presented through ‘normal’, every day means (letters, telegrams, diary entries). The extraordinary or ‘abnormal’ is ‘contained’ and presented through a façade of the ’normal’. The threat that ‘abnormality’ presents to society is safely enclosed and somewhat negated in the carefully ordered, compiled and edited product that the audience is permitted to access. However, the proximity of ‘abnormality’ creates a sense of unease, fear and dread and suggests that the socially designated categories of ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ are fluid and precarious.

Horror and disability studies may not seem to be natural allies, yet both explicitly challenge social understandings of the ’normal’ by exposing the concept as a constructed smokescreen designed to obscure distressing and frightening truths and realities. Disability theorists argue that the body is central to society’s understandings of ‘normal’ and that “normalcy is constructed to create the “problem” of the disabled person” (Davis 1). With this in mind, it is no surprise that initial studies of disabled individuals was named Teratology, a term originally understood to mean the study of monsters (Bogdan).

To instigate radical social changes around disability and remove the long-lasting stigmas that attribute monstrosity and evil to impairment, it is essential to “reverse the hegemony of the normal and to institute alternative ways of thinking about the abnormal” (Davis 12). Found footage horror’s ethos is to challenge normality by weaponising the ‘normal’ and using it as a medium to present the abnormal or the incomprehensible. Found footage must contextualise why events are being recorded to imbue it with ‘truth’ or ‘reality’ and revels in the mundane and habitual in order to subvert it. Terror is created through long shots of ‘normal’ incidences with the expectation that something ‘abnormal’ may happen. The audience are pre-conditioned to accept abnormality and are receptive to alternative perspectives regarding their understandings of truth, reality and designations of ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’. Found footage horror’s subversive and radical power emanates from the prospect of ‘abnormality’ transgressing its boundaries and acquiring autonomy. The genre creates a space where unsettling and oft-repressed ‘abnormal’ bodily realities such as Alzheimer’s disease and terminal illness intermingle with metaphorical manifestations of these distressing realities such as demons and demonic possession. The use of the everyday, ‘normal and mundane’ institutes a new mode of subversive and radical thinking outside of the status quo in which what is ‘abnormal’ can be explored and what is ‘normal’ can be challenged and if necessary, reconfigured.

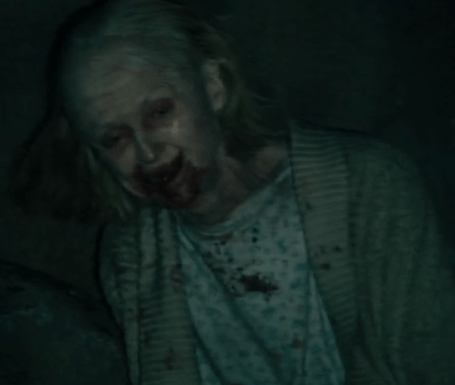

The Taking of Deborah Logan initially follows a medical documentary style format following a group of PhD student researchers documenting Deborah, an elderly woman, and her struggles with Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and Alzheimer’s are deeply uncanny as what should be comfortable and familiar, an individual’s own body and mind, become deeply unfamiliar sites of mystery, uncertainty and anxiety. The stigma and fear surrounding Alzheimer’s is widespread and “people over the age of 55 dread getting Alzheimer’s more than any other disease” (Hodge 212). The film brings a repressed fear of an ‘abnormal’ body directly into the audience’s reality. Deborah and her story are fictional but Alzheimer’s and the effects and impacts it has on identity, families, communities and ideas of ‘normal’ are very real. The viewer is confronted with the prospect of Alzheimer’s disturbing the habitual normality of their lives either through the possibility of developing symptoms themselves or having to provide care for a family member.

While Deborah’s Alzheimer’s is later conflated with demonic possession, from the outset the film exposes the uncomfortable truth that all bodies are subject to transformation. Everyone “is subject to the gradually disabling process of aging” and the fact that “we will all become disabled if we live long enough” is a reality many “are reluctant to admit” (Garland-Thomson 13-14). All bodies are subject to the passage of time and the loss of physical and mental faculties and the acquisition of disabilities is not ‘abnormal’ but actually natural and ‘normal’.

Deborah’s age and gender are explicitly foregrounded in the film’s opening scenes and she is presented as ‘other’ before exhibiting any traits of Alzheimer’s. Deborah refers to her initial noticing of her condition as having “senior moments,” normalising mental deterioration as part of the aging process and categorising herself within a social hierarchy. Mia, the primary documentarian, calls Deborah a “proper old lady” and designates her value through age and gender. Deborah’s daughter, Sarah, warns the students that “Ma can come off kind of salty but it’s all an act” and that “she’s excited you’re here” and that they should “kiss her ass”. Deborah is spoken of less like an adult but is infantilised by those younger than her and marginalised in her own home.

Deborah is introduced as an elegant, polite and articulate woman. Although suffering from a debilitating mental impairment, she is aware of and is able to perform a role of normalcy as a “proper old lady” and is aware of the traits that she has to mask to avert social stigma. However, Deborah’s lack of authority is revealed when she clearly and repeatedly articulates that she does not want to be involved in the documentary. She says “I’m not interested in being exploited”, “I’m not the butt of anyone’s joke” and “I think you would be better off with someone else. I’m sorry”. Deborah is suspicious as she is all too conscious of her age, condition and gender as well as a tradition of misrepresentation and exploitation of the aging female in film. While the film is connected to the genres of documentary and horror it also utilizes themes from the mid twentieth century subgenre of hagsploitation to make intertextual links and consider whether twenty-first century film’s representations of the aging female are fair or exploitative.

Hagsploitation was popularised by films such as Sunset Boulevard (1950) and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane (1963) which depicted aging women as psychotic and dangerous figures that inspire fear and revulsion. Hagsploitation draws from entrenched cultural stereotypes and prejudices that codify the elderly woman as an evil witch or crone preying upon the young. Maddie McGillvray in her exploration of the horrors of the aging woman has raised the fact that “the face of evil has often been that of an older woman” (McGillvray 70). Deborah is aware of her age and illness and wishes to avoid unfavourable representation which could depict her as a ‘monster’ inspiring fear and revulsion when she is actually a vulnerable human being with an illness in need of support and understanding.

The exploitation and cultural capital held over the elderly, vulnerable and infirm is made painfully apparent as Deborah is coerced into participating in the documentary. Mia lies to Deborah telling her that “my grandfather had the disease so it’s not just a grade for me.” As well as emotional manipulation, Mia knows she can also rely on financial intimidation, telling her crewmate “she’s behind on the house, but she won’t sell so Sarah’s in a tough spot.” Through the unedited ‘reality’ of the found footage style, the audience witnesses, and is by extension complicit in, the exploitation of an ill and susceptible member of society. The film’s opening moments expose the stigma, ‘othering’ and infantilisation of the aging body and poses troubling questions about the spectator’s own status, body and how they conform to or challenge normalcy.

The film details the horrors of Alzheimer’s and presents it as a monstrous entity. Mia explains that Alzheimer’s is an “insidious disease” that destroys “neurons responsible for logical thought and problem solving” and causes “terrifying hallucinations” while “erasing a person’s oldest and most precious memories”. The disease is personified as an evil presence that “creeps”, “assaults,” and “destroys.” Deborah does her best to manage her condition but recognises the futility of her efforts as “there’s no cure.” Deborah attempts to articulate her thoughts on her situation and says “there are no words to describe how distressing it is.” Illness and the loss of mental ability or bodily control is deeply disturbing and requires the use of metaphor in an attempt to express what may be inexpressible.

As Deborah begins to exhibit extreme behaviours that are uncharacteristic of Alzheimer’s, the film utilises tropes from the demonic possession genre to provide a comfortable distance from the realities of progressive illness. The ‘reality’ of the documentary style, the illness itself and the audience’s identification with the character of Deborah is almost too ‘real’ and so it is countered with a tonal ‘gear shift’ into the realms of possession horror. The illusion of reality is broken as the actualities of aging and impairment are overwritten by a fantastical plot involving demonic possession. It is notable that the film culminates with a demon-possessed Deborah abducting a young female leukaemia patient. Deborah becomes a complete demonic ‘other’ in that her behaviours are attributed to evil and the film uses CGI to manipulate Deborah’s face and jaw to make it snake-like and as if she is eating the young girl. The elegant Deborah of the film’s introduction is transformed by the film’s conclusion into the cultural stereotype of the evil witch or crone preying upon the young.

The film utilises established horror genre tropes to provide a façade of ‘normal’ and ‘contain’ the truly horrifying. This is for narrative and entertainment purposes to provide a satisfying catharsis and resolution. If Deborah’s transformation is due to a supernatural or magical cause, it can be resolved through supernatural or magical means. The film’s conclusion involves a ritualistic exorcism to remove the evil entity from Deborah. This provides a narrative closure or ‘victory’ over the demon, but as Deborah tells us herself, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s and the ‘magic’ of medical intervention can only facilitate management of the condition.

Representing Deborah as a demonic ‘other’ inhibits identification with her as a severely ill human being. Demonic representation negates her illness but also the subversive and repressed reality that all bodies are subject to aging, impairment and disease. While the film may re-enforce notions of normalcy as Deborah is transformed into a monster by the film’s end, the film also implies that the young girl’s leukaemia is cured and that this is due to demonic intervention. If demonic possession is used as a metaphor to explore the horrors of illness and a loss of physical and mental control and agency, the fact that the ‘demon’ is not eradicated at the end of the film highlights the potential of one’s own ‘possession’ or ‘taking’ through illness or even the distressing nature of the natural processes of aging.

While the film focusses on the bodily horrors suffered by Deborah, it also foregrounds the role and importance of the caregiver and how society should respond to its most vulnerable members. Early in the film, Mia talks of the disease’s “psychological influence on the primary caregiver”. While Sarah, Deborah’s daughter, is implicated in Deborah’s exploitation, her intentions are ultimately good and consider her mother’s best interests. Sarah persuades Deborah to participate in the documentary in order to pay for healthcare and to be able to keep her house. The documentary provides a means to earn money that will be used to support Deborah. Sarah is faced with the many difficult choices a caregiver must face in order to support a terminally ill and vulnerable relative or member of their community. Even when the narrative shifts from illness to demonic possession, Sarah never withdraws her support and attempts to aid her mother despite the unexpected twists and turns of Alzheimer’s and transformation into a monstrous ‘other’.

The Taking of Deborah Logan uses the found footage format to manipulate boundaries around ideas of ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’, truth and fiction. These ideas are expressed through the body and attitudes towards aging, illness and impairment. The format manipulates the audience’s understandings of ‘normal’ and exposes it as a construction to hide subversive ideas around aging, illness and disability. The Taking of Deborah Logan forces the audience to relate to and empathise with an elderly woman losing control of her body and mind to a degenerative illness. The horror of losing control of one’s own body is further explored through the use of the familiar trope of demonic possession to act as a metaphor for illness and a loss of normalcy. The Taking of Deborah Logan forces the audience to consider the possibility of their own aging body and potentiality for disability and impairment. This empathy causes a disruption of the construction of normalcy and institutes new ways of viewing disability. While Deborah represents the fear of illness and aging, Sarah offers an example of an engagement with the realities of disability and the need for understanding, care and support of the impaired and vulnerable in society. Sarah challenges the audience to consider their own role in supporting those with impairments as well as modelling the care and support every individual should hope to receive as they age and require assistance to live with integrity and dignity.

Works Cited

Bogdan, Robert. Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit. University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Davis, Lennard J. “Introduction: Disability, Normality, and Power.” The Disability Studies Reader Fourth Edition, edited by Lennard J. Davis, Routledge, 2013, pp. 1-16.

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature, Columbia University Press, 1997.

Heller-Nicolas, Alexandra. Found Footage Horror Films: Fear and the Appearance of Reality, McFarland, 2014.

Hodge, Stephanie. “Demonizing Dementia in Horror: How Hollywood Plays on ‘Fears of Forgetting.’” Exploring the Macabre, Malevolent, and Mysterious: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Matthew Hodge and Elizabeth Kusko, Cambridge Scholars, 2020, pp. 211-229.

McGillvray, Maddi. “’To grandmother’s house we go’: Documenting the Horror of the Aging Woman in Found Footage Films.” Elder Horror: Essays on Film’s Frightening Images of Aging, edited by Cynthia J. Miller and A. Bowdoin Van Riper, McFarland, 2019, pp. 70-80.

The Taking of Deborah Logan. Adam Robitel, director. Eagle Films, 2014.