Adam Daniel

Released in late 2020, Immortality, the new FMV (full-motion video) game by developer Half Mermaid and creator Sam Barlow generated a wave of laudatory reviews and was rightfully celebrated as one of the more audacious and thematically complex uses of the form to date. In his previous games Her Story (2015) and Telling Lies (2019), Barlow has demonstrated a keen fascination with the potential intersections between cinema and interactive gaming, establishing a reputation as a trailblazer in the genre. He continues this evolution with Immortality.

As the writer and designer of two entries in the Silent Hill gaming franchise, Silent Hill: Origins (2007) and Silent Hill: Shattered Memories (2009), Barlow has demonstrated a clear love of the horror genre. In Immortality, working in conjunction with Allan Scott (Don’t Look Now (1973), The Queen’s Gambit (2020)), Amelia Gray (Mr. Robot (2015), Maniac (2018)) and Barry Gifford (Wild at Heart (1989), Lost Highway (1995)), Barlow returns to the genre with a clear desire to destabilise and unnerve the player through an original and provocative utilisation of the expanded properties of the interactive gaming medium.

A mystery lies at the heart of the game, which presents as a three-decade long repository of the work of fictional actress Marissa Marcel. Marcel’s enigmatic disappearance is the game’s core puzzle. In the game’s preamble, Barlow provides ‘A Short History of Marissa Marcel,’ which outlines the premise in a manner that is reminiscent of many found footage horror films:

In 1968, many thought Marcel would become a huge star, but these days she is largely forgotten. A few dedicated enthusiasts have attempted to find her lost movies and floated their own theories of ‘What happened to Marissa Marcel?’. To no avail. Then in 2022, a breakthrough. A large cache of film was discovered containing footage from all three of Marcel’s movies. After carefully collating and scanning the footage, we have created this piece of computer software in an attempt to preserve this work and share it so that Marissa may live again in the hearts of audiences. (Barlow)

In this way, Immortality continues the horror genre’s long history of claims to the veracity of the events depicted, usually done with the intent of intensifying a viewer’s curiosity and interest. In films such as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Wolf Creek (2005), The Amityville Horror (1979) and The Conjuring (2013), false assertions are made to the recreation of ‘actual events,’ with claims of authenticity designed to heighten the immersive properties of the narrative. Found footage horror often goes beyond this, however, with claims that the events presented are actual documentation of real people and events. As Cecilia Sayad describes, they are often presented as “a fragment of the real world,” with the implication that their content has tangible connections to the world outside of the film (Sayad 45). The prevalence of this realist impulse in the horror genre is clearly apparent in the rising prominence of found footage horror from the late 1990s through to the present day (Heller-Nicholas).

Immortality convincingly stages this premise through the content that is provided to the player: raw footage from Marcel’s three unreleased films, and an array of behind-the-scenes recordings, interviews, paratextual materials, and rehearsal footage. The films include a scandalous period tale, Ambrosio (1968), shot in Italy and featuring provocative and often titillating material common to the low-budget European cinema of the late sixties; Minsky (1970), a pulpy New York crime thriller featuring a complicated psychosexual dynamic between a detective and his suspect; and Two of Everything (1999), a slick, digitally shot mystery drama with Lynchian allusions. Players access these clips through a Moviola-style software engine that allows them to be played at various speeds, both forward and backwards.

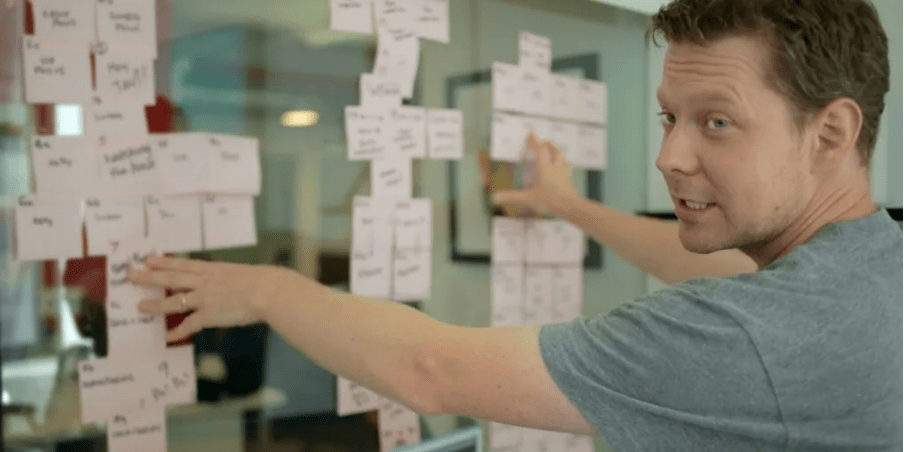

Where Immortality progresses from Her Story and Telling Lies is in the game’s introduction of the “match cut” mechanism to move between clips. While these earlier games were dependent on the player identifying and using keywords to navigate through clips, the “match cut” mechanism in Immortality allows the player to click on various characters or objects within the clip, which immediately transitions the game to a new clip (leaping across film projects and sometimes even across decades). For example, when the player clicks on a knife held by a character in one clip, the game launches them into another clip that also features a knife (although not necessarily the same knife). This intricate web of semiotically-linked materials draws the player deeper and deeper into the game, making them equal parts voyeur and detective.

A diligent exploration of these clips eventually reveals a layer of narrative hidden underneath their surface, a narrative imbued with ambiguous and eerie properties. It is here where I think the game most clearly embraces some of the spectatorial appeals of found footage horror, and in continuing this discussion I will seek to analyse how Immortality not only deploys certain conventions of found footage horror cinema, but also capitalises on how the interactive elements of the video game medium contribute to the production of a specific affect.

As previously described, the core mechanic of the game is the player’s navigation through the archival materials. However, not all materials are made immediately available. It is through the use of the “match cut” mechanism that clips gradually become accessible, and it is up the player to make sense of them (and also to construct their own understanding of the narrative content of each film, given that the provided clips are fractured by the chronology of film production, which often shoots material out of sequence). Depending on where the match cut is made, the player may also find themselves at any temporal point in the clip, which encourages a movement both forward and backwards through the materials presented. Like found footage horror film, the game rewards attention to detail and eschews the temporal economy of conventional cinema. Many of the clips are of an extended duration and present as narratively disconnected or unfocused; however, like found footage horror, this unconventional duration contributes to the building of an affect of dread, which I see as a core emotional component of many films of the sub-genre (See Daniel, chapter 3). The gameplay also draws on some of the general appeals of found footage horror in that the viewer is often presented with an excess of visual content and must parse the material for that which is important to the narrative; in the game, this includes seeking out potential items to use through the match cut mechanic which may open unique narrative pathways.

The verisimilitude with which the archival materials have been created also contributes to the pleasure of the experience. The central performances are impeccable and captivating, in both the film and extra-filmic materials, particularly that of Manon Gage as Marissa Marcel. Like many successful found footage projects, they encourage the viewer to “indulge in an active horror fantasy, one where (they) can knowingly accept and embrace the real-seeming film frame” (Heller-Nicholas 8). In doing so, the mystery of Marcel’s eventual disappearance and the reasons each film was not released become more tangible and also somewhat inexplicable. The apparent authenticity of Marcel’s films encourages an audience indulgence in the false mythology presented by the game, in much the same way The Blair Witch Project (1999) encouraged a similar audience indulgence at the time of its release.

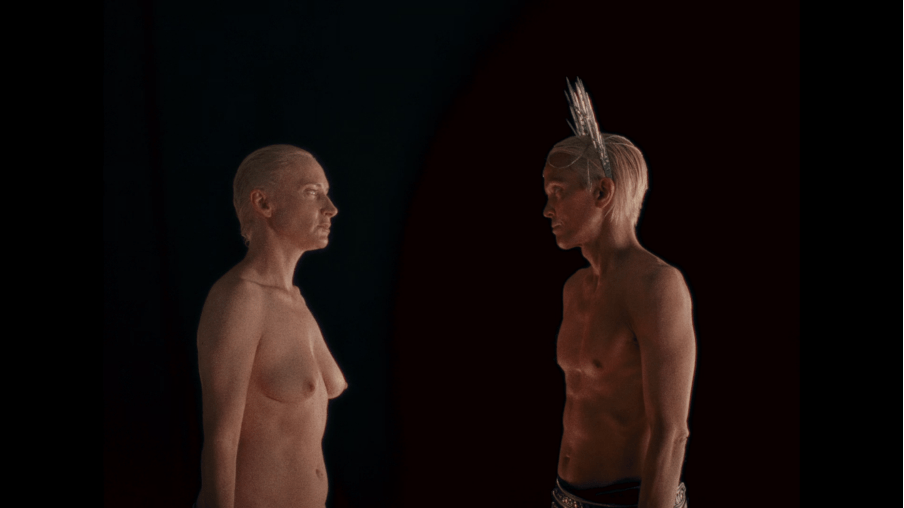

Alexandra Heller-Nicholas argues that within the genre of found footage horror “if nothing seems to happen, it does so in strategic ways” (Heller-Nicholas 8). This is certainly a core aspect of the early gameplay of Immortality, until this mundanity is punctuated and the footage the player is reviewing is revealed to be not at all what it seems. An ominous sound cue in certain clips encourages the player to alternate the playback direction, and in doing so, they unveil sinister alternate footage ‘underneath’ that which has been previously witnessed. In these clips, Marcel and her fellow cast members are often replaced by one or two ethereal, androgynous figures. Known in the game’s credits as The One and the The Other, these quasi-immortal supernatural figures offer a commentary on mortality, the creative process, and humanity’s purpose. Upon their reveal, the gameplay shifts into a search for more traces of their presence within the archive.

The presence of these entities haunts the footage that the player scours through. While haunting is often understood as a form of temporal dislocation, or the emergence of something from the past manifesting in the present, contemporary scholarship of hauntology expands this understanding by arguing that haunting may unveil the contingency of experience; the ‘ghost’ may go beyond being a revenant of the past, to being that which disrupts the stability of the present by indicating that there are potential alternative narratives underneath the surface of putative events (del Pilar Blanco & Pereen). Immortality literalises this expanded conception of haunting. Following the revelation that certain of these archival clips are palimpsests is another revelation; that other previously viewed clips are also now infected by ghostly doubles of The One and The Other, superimposed over the bodies of the cast or the frame as a whole.

Superimposition has a long history as a signifier of the supernatural. While Bazin argued that superimposition in cinema fails to integrate two levels of reality, and thus fails to truly evoke the supernatural, I contend that the superimpositions offered by the game are radically effective in this regard (Bazin 74). The superimposed image creates what Gene Youngblood labels a “synaesthetic cinema” through its fusion of the “endotopic” (inside) and “exotopic” (outside) elements of the picture plane, and the resulting depth of field of the image produces a “nonfocused multiplicity” (Youngblood 85). Within this multiplicity are the unresolved qualities of a profound haunting, in the sense that Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock uses to describe it: that which indicates that “beneath the surface of received history, there lurks another narrative, an untold story that calls into question the veracity of the authorized version of events” (Weinstock 63). This is especially potent for a narrative that is thematically concerned with the unspoken power dynamics and sexual politics of the film industry.

The aural qualities of the infected clips mimics this emphasis on the power of the superimposition to destabilise diegetic coherence. Michel Chion uses the term ‘acousmatic’ to describe one way in which sound and vision can be strategically detached from each other (Chion 465-6). It describes an auditory situation in which we hear sounds without seeing their cause or source. In the further exploration of the archive after these supernatural entities have been revealed, a low sonic rumble cues the player to their unseen presence. The potential instability of all previously seen materials incites the player to hunt for these aural cues, searching for novel ruptures in the Marcel filmography.

This destabilisation of the archive produces for the viewer an epistemological uncertainty that is often key to the genre of horror. However, this ambiguity is less commonly deployed in found footage horror, which attempts to incite audience identification through the authenticity claims and verisimilitude of the documentary form. It is through the synthesis of these elements—the assertions to authenticity of the Marcel archive and the contradictory presence of the haunting (and its epistemic destabilisation) that Barlow has constructed a unique and captivating horror experience. As a hybrid of cinema and gaming, Immortality adds a fascinating new dynamic to the act of found footage horror spectatorship.

** Immortality is available on Xbox Series X and Series S, Android and iOS (through Netflix Gaming), macOS, Microsoft Windows, and Mac operating systems.

Works Cited

The Amityville Horror. Directed by Stuart Rosenberg, American International Pictures, 1979.

Bazin, André. “The Life and Death of Superimposition.” Bazin at Work: Major Essays and Reviews from the Forties and Fifties, trans. Alain Piette and Bert Cardullo. Routledge, 1997.

The Blair Witch Project. Directed by Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, Artisan Entertainment, 1999.

Chion, Michel. Film, a Sound Art. Columbia University Press, 2009.

The Conjuring. Directed by James Wan, Warner Bros. Pictures, 2013.

Daniel, Adam. Affective Intensities and Evolving Horror Forms: From Found Footage to Virtual Reality. Edinburgh University Press, 2020.

del Pilar Blanco, María, and Esther Peeren, editors. The Spectralities Reader: Ghosts and Haunting in Contemporary Cultural Theory. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013.

Her Story. Windows, Sam Barlow, 2019.

Heller-Nicholas, Alexandra. Found Footage Horror Films: Fear and the Appearance of Reality. McFarland, 2014.

Immortality. Windows, Half-Mermaid, 2022.

King, Andrew. “Interview: Sam Barlow talks Movie Mystery Game ‘Immortality’, ‘Inland Empire’ Inspiration and the Spiritual Successor to His ‘Silent Hill’ Game.” Bloody Disgusting, 24 June 2021.

Sayad, Cecilia. “Found-Footage Horror and the Frame’s Undoing.” Cinema Journal, vol. 55, no. 2, 2016, pp. 43-66.

Telling Lies. Windows, Sam Barlow and Furious Bee, 2019.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Directed by Tobe Hooper, Bryanstown Distributing Company, 1974.

Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew. “Introduction: The spectral turn.” The Spectralities Reader: Ghosts and Haunting in Contemporary Cultural Theory, edited by Maria del Pilar Blanco and Esther Peeren, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013, pp. 61-68.

Wolf Creek. Directed by Greg McLean, Roadshow Entertainment, 2005.

Youngblood, Gene. Expanded Cinema. P. Dutton & Co, 1970.