A repeated visual motif in some recent horror films (actually ecohorror films) is the landscape that engulfs characters. These moments typically involve extreme long shots in which the characters are swallowed by their surroundings. They highlight, most obviously, the insignificance of humans in the face of an overwhelming nature. But they also represent, more ominously, how nature seems to be actively encroaching on the characters, actively threatening them. What happens in these moments is, I think, a distinct variant of ecohorror.

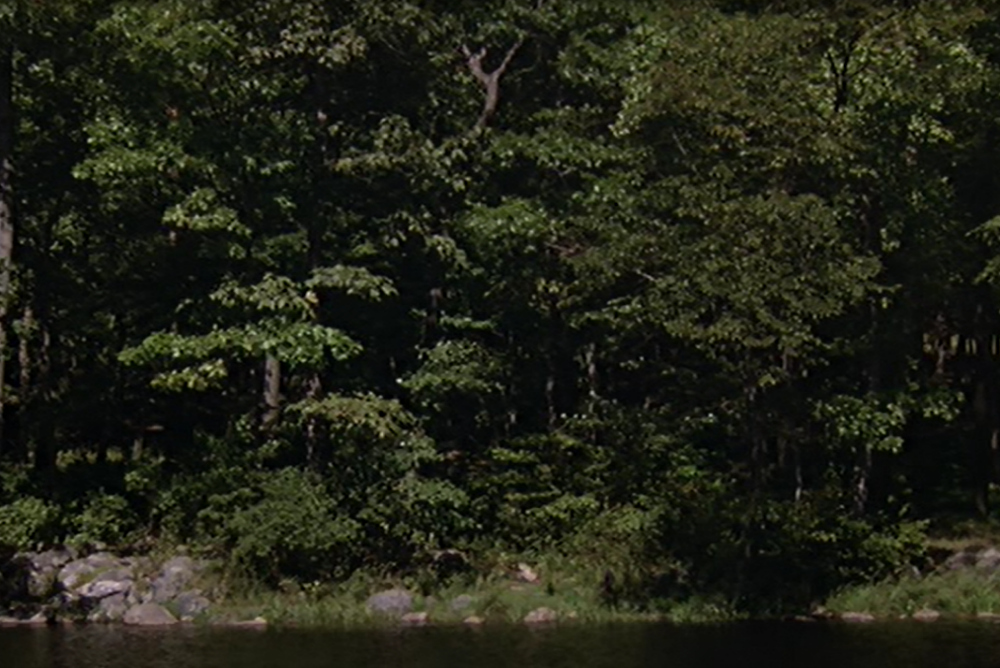

Notice how in all the shots below, you can barely see the human characters at all (Figs. 1-4).

In these instances, nature seems to be launching what could be called a monstrous revolution. Evan Calder Williams has written that The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974) stages the “insurrectionary prospect of the background coming monstrously into its denied prominence.”[1] Nature refuses to remain mere back-drop, contesting the supremacy of the human. The background looms to the fore, the humans are diminished, and nature seems as menacing as the monster itself (Fig. 5).

Indeed, in some more recent films, nature vanquishes the human entirely, remaining alone in the frame (Figs. 6 & 7).

As nature usurps the frame in these ecohorror moments, the distinctiveness of the human gets eroded. All those attributes and characteristics that have allowed us to think that we stand out from the rest of the natural world, unique—those characteristics that allow us to seize the foreground—become attenuated. As nature impinges, it urges the recognition that we are just another part of nature. The closer nature get, the more it swallows up the frame, the more this threat intensifies. We merge into what was our background, indistinguishable (Fig. 8).

So what does this mean? Why is nature moving so inexorably into the foreground in these horror films? In his recent book, Why Horror Seduces, Mathias Clasen of Aarhus University in Denmark makes the argument that horror appeals to so many of us because our long evolutionary past causes us to respond in certain ways to certain stimuli. We’ve had to be alert to predators, for instance—predators often lurking in the forests and jungles where our ancestors lived. The domains of entangled plants, vines, trees, and bushes—where we can’t see well, where beasts may be lying in wait—are just frightening. Seeing vegetation swarming the foreground, then, activates hard-wired human fears.[2]

I want to propose, though, that these “ecohorror” moments in the recent horror film are also causally related to the emergence since the 1980s of what neuroscientists and cognitive psychologists have called the “cognitive unconscious.” This new kind of “unconscious” lives in the brain, for the most part, in neurons and synapses, and it encompasses the myriad kinds of mental processing that go on without our conscious awareness. In 1999, in the journal American Psychologist, John Bargh and Tanya Chartrand wrote that “most of daily life is driven by automatic, nonconscious mental processes.” And work in psychology and neuroscience has only proliferated in the decade and a half since they wrote those words, uncovering more and more of what they call “the unbearable automaticity of being.”[3] Study after study is disclosing, as one study puts it, how much of “our everyday behavior is controlled by automatic processes that unfold in the complete absence of consciousness.”[4]

While the cognitive unconscious is quite different from the psychoanalytic unconscious, the most famous proponent of the psychoanalytic unconscious, Sigmund Freud, actually recognized the presence of automatic processes in his 1919 essay, “The Uncanny.” He fleetingly described how “epileptic fits” and other “manifestations of insanity” seem uncanny because they “arouse in the onlooker vague notions of automatic—mechanical—processes that may lie hidden behind the familiar image of a living person.”[5] Freud’s brief reference to automatic processes lying “hidden behind” the “person” anticipated the discoveries of psychologists of the last three decades. It presciently marked how we often act automatically, mechanically, without knowledge and volition—and how this buried automaticity is uncanny, how it makes us “strangers to ourselves” (in the title of a recent book).[6] While we may like to think of those automatic processes “hidden” within ourselves, all those neurons and synapses, as serving what we choose to do, the new sciences of the mind put those automatic processes in control.

M. Night Shyamalan’s The Happening (2008) wonderfully illustrates how the swelling of nature—of plants, bushes, vines, trees—into the foreground seems inextricably linked to the subsuming, even destruction, of the “autonomous” human, in control of what he or she does. The encroachment of nature in The Happening coincides with strange, sudden acts of mass suicide. Humans inexplicably start immolating themselves with whatever is at hand: they leap from buildings, lay down in front of lawnmowers, and hang themselves from trees (Fig. 9). The theory posed by “experts” in the film is that plants are releasing a chemical that disables some mechanism of self-preservation in the human brain, though what’s really happening is never definitively explained. For my purposes, though, what The Happening brilliantly does is link the emergence of nature (from background to foreground) with utterly nonconscious human actions—that is, automatic, reflexive, unthinking actions that are triggered by nature “out there” and by nature inside, by something in the brain. This ecohorror film, in other words, links nature with the new cognitive unconscious. The Happening shows that when “nature” presses forward, longstanding understandings of humans as separate, dominant, and autonomous inexorably recede.

The theory of a particular kind of ecohorror that I’ve laid out here—the nature of horror, the “new” unconscious of horror—is something I’ll be tracking in other films in future blog posts. So, stay tuned!

The Happening is on Blu-ray and streaming on Amazon:

[1] Evan Calder Williams, “Sunset with Chainsaw,” Film Quarterly 64.4 (2011).

[2] Mathias Clasen, Why Horror Seduces (Oxford University Press, 2017).

[3] John Bargh and Tanya Chartrand, “The Unbearable Automaticity of Being,” American Psychologist 54.7 (1999).

[4] Tillmann Vierkant, Julian Kiverstein, and Andy Clark, “Decomposing the Will: Meeting the Zombie Challenge,” in Decomposing the Will, ed. Clark, Kiverstein, and Vierkant (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

[5] Sigmund Freud, The Uncanny (Penguin, 2003).

[6] Timothy D. Wilson, Strangers to Ourselves: Discovering the Adaptive Unconscious (Belknap Press, 2004). See also David Eagleman, Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain (Vintage, 2011) and Kristof Koch, Consciousness (MIT Press, 2012).

Follow Horror Homeroom on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Pinterest.