In a previous post, I wrote about how Barbra’s ability to see in Night of the Living Dead (1990) aligns her with the monster. Upon rewatching Tom Savini’s remake, I was struck by how the characters as a whole disrupt the audience’s expectation of behavior attributed to females. To understand how Barbra employs a uniquely androgynous form of killing, we must consider her in relation to the other women who occupy the house. Unlike Helen who has Harry, and Judy Rose who has Johnny, Barbra is not sexually linked to any male in the house. This sexual independence marks her, like a monster, as abnormal. Also entering the equation is how each female is situated to represent an aspect of the feminine.

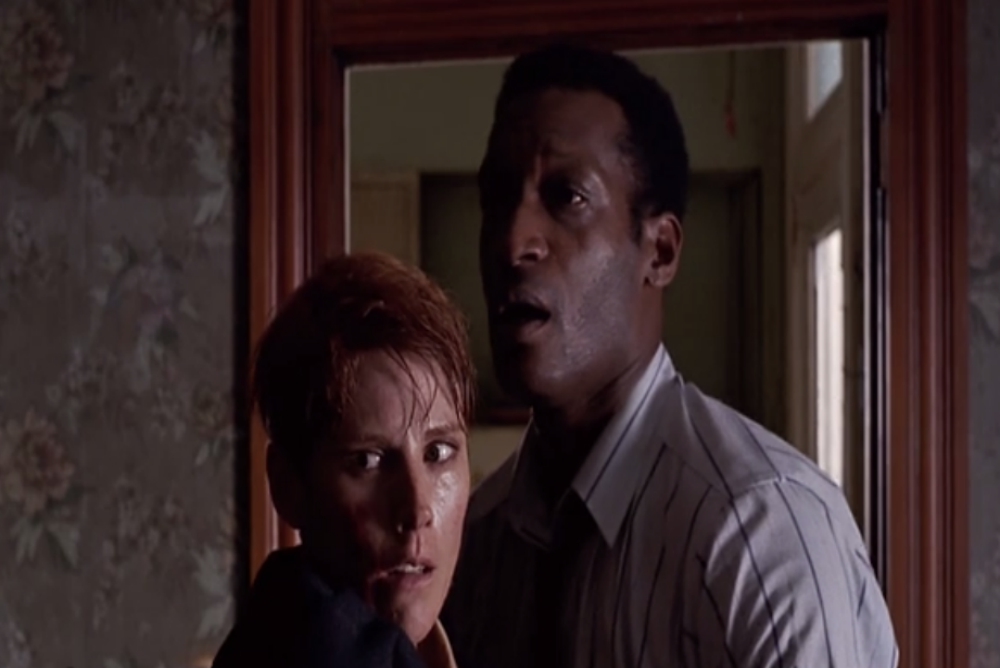

Barbra’s function in Night of the Living Dead (1990) is to illustrate the power to be derived from androgyny, from breaking free of social confines. Her boots and trousers are a deliberate visual contrast to Helen’s conservative dress and pearls. Also at odds between the two characters is their response to Sarah, Helen and Harry’s daughter who has been injured. Helen’s role as mother is portrayed as destructive when it is implied that Harry is abusive. When she does finally get the courage to fight back against Harry, Helen is cajoled back into the family dynamic when he tells her that their daughter needs her. It is Helen’s love for her daughter that blinds her and prevents her from seeing the threat posed by the girl. This feminine need to mother is never evident in Barbra. While Ben, Judy Rose and Johnny all inquire as to Sarah’s health, Barbra never does. She remains able to see because she is not hampered by the feminized imperative to be responsible for another.

Sarah also functions as a means of exploring Barbra’s turn toward the masculine. The costuming of Sarah is very deliberate. While she wears the outfit of a young child (party dress, ruffled socks and patent leather shoes), she is clearly, by virtue of her height and braces, on the cusp of womanhood. In a moment laden with gender subtext, the androgynous Barbra kills the feminized child. Sarah’s straddling of two identities, child and woman, leaves her in a suspended state when she dies. But for Barbra, who has claimed her masculine power, this is no such struggle.

Similarly, Judy Rose’s need for continued affirmation sets her apart from Barbra. Judy Rose spends the majority of her time in Night of the Living Dead (1990) either panicking or disapproving of Barbra’s aggression. Even the one moment of agency for the character, when Judy Rose insists against male voices that she knows how to drive the truck, is compromised because it take the agreement of Johnny for her to be heard. This is a subtle moment in the film because it hints that Judy Rose may be aware of her lack of authority—and so she implores Johnny to give her credibility, demanding he tell them she is capable. Still, any development in Judy Rose’s personal power is thwarted when, upon successfully getting the car to start, she panics and threatens Ben’s safety by driving erratically. She becomes the quintessential panicking female whose own fear renders her incapable of ever seeing like Barbra does.

The question of Barbra’s sexuality is addressed before the audience ever meets her. As we watch the car drive into the cemetery, we hear her brother, Johnny, mock her lack of dates. This implies a distinct absence of sexuality that allows us to think of Barbra as just outside of feminine ideals. Viewing her as not wholly female then makes it that much easier for the audience to accept the masculine traits she exhibits later in the film. Interestingly, there is a moment when Barbra’s sexuality works in concert with the monstrous, a role that is not occupied by the zombies. Instead, having fled the house, Barbra is surrounded by some good ol’ boys with the implication that perhaps she has far more to fear from their violent masculinity than she does from the zombies.

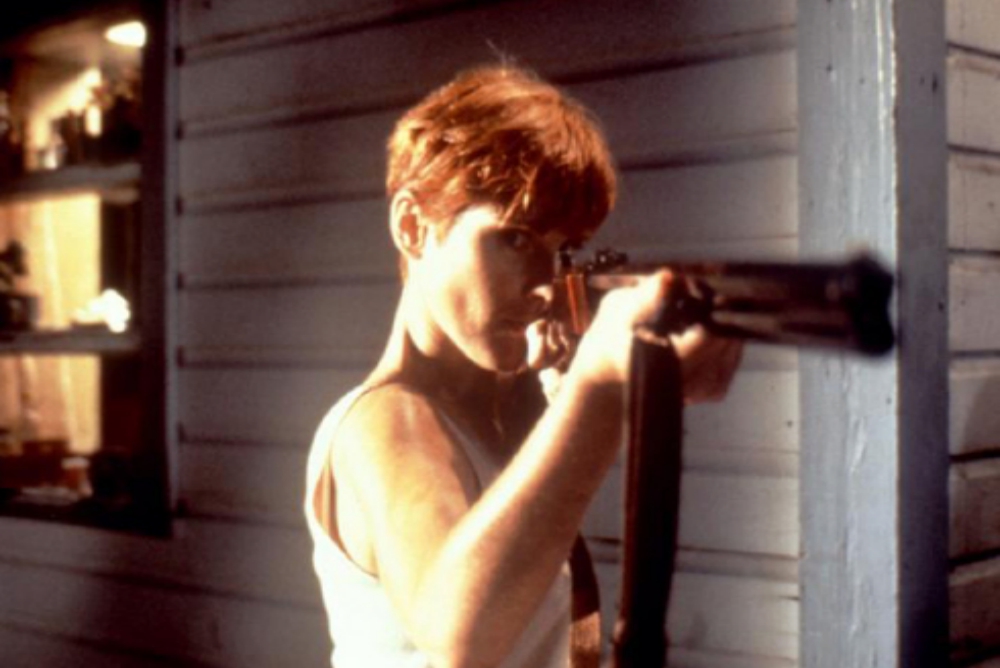

In addition to the marked change in costume when the character forgoes a skirt and heels in favor of boots and trousers, Barbra wears a severe haircut and has an extremely lithe body type that does not curve in an appropriately feminine manner. Yet, more importantly, it is her mannerisms and knowledge that truly suggest androgyny. Upon finding the guns, Barbra is able to load and shoot without any instruction from the males in the house. This indicates a comfort with guns not commonly associated with the feminine. Clover describes how the feminine and masculine function in horror:

Angry displays of force may belong to the male, but crying, cowering, screaming, fainting, trembling, begging for mercy belong to the female. Abject terror, in short, is gendered feminine, and the more concerned a given film is with that condition—and it is the essence of modern horror—the more likely the femaleness of the victim.

The moment Barbra shoots Harry she has adopted the masculine since this killing is not born out of need but desire. Interestingly, this adoption of the masculine is only possible thanks to another moment in the film that also speaks to the struggle between engendered perceptions of violence. When Ben says to Barbra, “I know you can fight when you have to,” he is, in effect, giving her the male seal of approval to break her engendered training in passivity.

You can read about social commentary in Night of the Living Dead (1968) here.

Night of the Living Dead (1990) is streaming on Amazon: