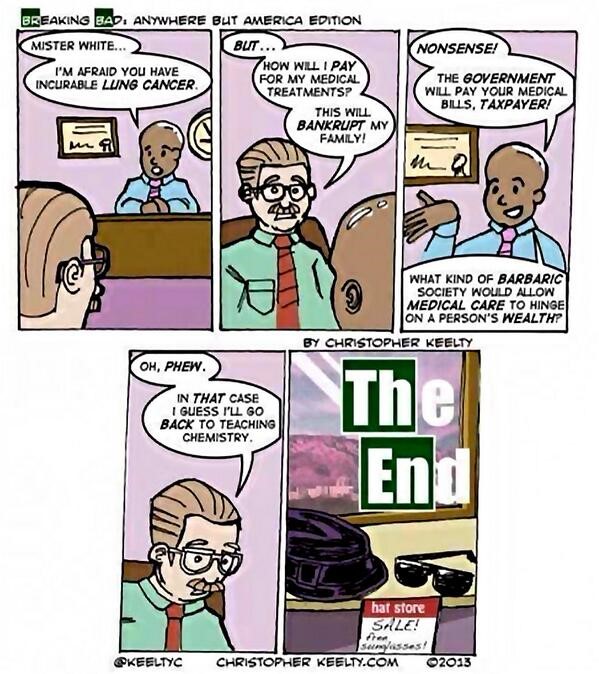

I recently came across a web-comic that satirised the premise of Breaking Bad. The gist of it is that Breaking Bad would never work in a country with free healthcare, since Walter White’s impetus for selling drugs is to cover the exorbitant cost of his cancer treatment.

Christopher Keelty, https://christopherkeelty.com/2013/09/breaking-bad-outside-us/

Now this is arguably an oversimplification, but it is funny nonetheless and does illustrate how neoliberalism is often a driving force behind films and series. This is especially so if the media in question is a US-based production where the liberal ideology of individual choice, meritocracy, and pulling oneself up by their bootstraps is firmly entrenched in the larger social consciousness. In the US, you are the master of your own fate, and you don’t need a handout. Now while it might not, at first glance, appear to be the case with the Saw franchise, the series has a deeply entrenched philosophy of aggressive individualism that covertly celebrates liberalism and glosses over systemic and societal factors underpinning many social ills.

On its surface, the Saw films play very much like a modernised version of fairy tales, complete with life-affirming morals: Don’t be mean, don’t steal, don’t take life for granted and so on, albeit with more violent repercussions should they be ignored. Little Red Riding Hood was not forced to walk barefoot over hot coals as some symbolic punishment for choosing to take a shortcut to grandma’s house. But beneath its moral exterior the Saw movies seem quite eager to punish those whose failings are arguably more complex than a simple choice to be reprehensible.

John Kramer, a.k.a. Jigsaw (Tobin Bell) is the moral adjudicator who metes out his warped version of “the punishment fits the crime” based on a philosophy that people who stray from the path of living an upstanding life can only be brought back through torturous games meant to re-instill a value for life. The assumption is thus that everyone has the same capacity to value their lives and they just need a little, violent, push. To value one’s life is a simple mental reset away. It’s like “The Secret” but with mutilation.

Yet, throughout the series, Jigsaw’s victims are predominantly working-class people who have arguably not had those opportunities and resources which make valuing life a whole lot easier. The films make it clear that Kramer himself had money, a successful career, access to resources (I imagine his trap budget alone must be rather exorbitant) and that his life-changing, near-death moment was not forced upon him, but rather brought about by a near-fatal car accident. From this perspective, he appears less like a life coach, and more like an egotistical millionaire with an “I know what’s good for poor people” vanity project.

As an example, the series has a propensity to put drug users in Jigsaw’s crosshairs. Jigsaw views drug usage as largely choice-based, despite the fact that several of his victims could trace their drug usage back to their (often wrongful) time in prison. But the literature (Branch 2011) surrounding addiction does not paint such a clear picture. The dialogue between choice vs. it’s a disease has not reached a consensus, suggesting something considerably more complex than the popular assumption that addiction is due to weak moral fibre (Hill 2019). There is also no guarantee that a traumatic near-death experience will automatically cure addiction. According to Hinders (2022), many overdose survivors suffer from ensuing survivor guilt which can lead to a continued drug use in order to numb the guilt. It is also fair to assume that surviving a Jigsaw “therapy” session can lead to PTSD and potential drug abuse as a side effect.

Victims of spousal abuse are also portrayed as simply lacking the self-confidence to walk away from their abusers. Both Morgan (Saw IV), and Sydney (Saw 3D) are forced into Jigsaw’s traps because, by his logic, they chose to endure their abuse instead of doing something about it. Again, research (Whiting 2016) around abuse points to multiple psychological and systemic factors which makes “just walk away” a rather facile argument. The fact that abuse often continues even after the victim has left the relationship is a testament to that fact (Gillis 2022).

The biggest departure from the overarching theme of punishing victims for their individual failings comes through in 2021’s Spiral: From the Book of Saw, the ninth entry in the franchise. This felt like the Saw film made for a post-George Floyd US. Here, the victims are all police officers, and all of them deeply corrupt. This feels like the only film in the franchise that comes close to addressing systemic failings instead of individual ones. It obviously does not go the full distance, however, and still seems to fall back on the “only a few rotten apples” defence.

I was wondering if maybe Saw X would follow this social consciousness thread, but I imagine the poor box office performance of Spiral scared producers back to the franchise’s well-trodden path. Saw X, while adding character depth to Jigsaw, is a return to the more reliable formula. There was, though, one moment of thematic awareness when Amanda (Shawnee Smith), Jigsaw’s accomplice who was herself a drug addict, tells Kramer that drug use and addiction are not always a choice, but this is promptly pushes aside with a “we all have a choice” counter, which settles the matter.

We should, however, also remember the role of the audience in all this. Some (or most) of Jigsaw’s victims are simply, as per audience expectations, not meant to survive. Their sins are far too reprehensible, and the horror genre has a long history of punishing those who “deserve” it. Abusers, scam artists, the corrupt – their deaths all feed into a primal obsession whereby death is the ultimate, and only, form of acceptable justice. It is an idealist interpretation of the death penalty whereby all moral situations are starkly black and white, with the bothersome grey area nowhere to be found. The unforgivable sin is conveniently individualised, and death solves the problem, no questions asked. Then there is also something considerably simpler: just wanting to see Jigsaw’s cool Rube Goldberg-esuqe traps inflict their inventive form of violence on human bodies. It’s the Chekhov’s Gun of gore: don’t show me an iron maiden filled with bees and snakes and expect me not to want to see it in action.

But this is, ironically, also where the franchise’s own ideology runs into some cognitive dissonance. It does not matter if certain victims make breakthroughs and realises their mistakes: their deaths are a foregone conclusion. In Saw 3D, main victim Bobby Degan (Sean Patrick Flanery) is put on the usual Jigsaw-style trial for building a successful career as a motivational speaker based on a lie that he was a Jigsaw survivor. His last test was to pierce his pectoral muscles with meat hooks and hoist himself to reach and connect a cable which will free his very innocent wife from a trap. Of course, Jigsaw assured him his muscles would be able to support his weight, yet inches from his goal, they inevitably fail. His failure is a failure of biology, not his own doing. No matter how much he deserved to succeed, his will and personal motivation is no match for an audience who really just wants to see what the final trap does which, till that point, had been constantly teased but never properly explained.

Now whether or not this predestined failure is some meta-textual awareness on the part of the franchise, the fact that some deaths are a given based on factors entirely beyond the control of the victim is a pretty big indictment of the liberal philosophy and its celebration of meritocracy. You can work your fingers to the bone, add unpaid overtime on top of unpaid overtime, sleep under your office desk, and sustain yourself on coffee and cigarettes, but in the end, you’ll never be the next Elon Musk simply because you never had the connections, generational wealth, or the luck to have been born white in Apartheid South Africa. The choice will never be yours to make.

Maybe Saw XI will reverse this trend and we’ll suddenly have Kramer, or one of his many protégés, running for public office hoping to make some real changes to the system through lobbying, instead of lobotomising. But if more than eighty years of Batman has taught me anything, is that audiences prefer Bruce Wayne punching his problems away instead of using his considerable wealth to enact real change.

Stefan Kriek is a part-time lecturer at the University of Johannesburg’s department of Communication and Media. He is currently neck deep in his PhD which centres on the racialized monster in the Candyman movies (even the bad ones). He doesn’t have a ton of writing under his name, but you can check out his talk on cyborgs and posthumanism.

Works Cited

Branch, M.N.(2011). Drug addiction. Is it a disease or is it based on choice? A review of Gene Heyman’s ‘Addiction: A disorder of choice’.

Gillis, K. (2022) 10 Common Stereotypes About Domestic Violence

Hill, T. (2019) Is Addiction a Choice?

Hinders, D. (2022) How to Deal With Survivor’s Guilt After an Addiction Overdose

Whiting, J. (2016) Eight Reasons Women Stay in Abusive Relationships